| IN SEARCH OF NEW BEGINNINGS

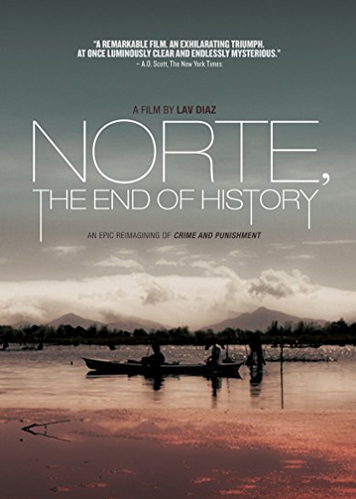

an essay by gil quito Considering that the film medium depends so much on man-made light, it’s somewhat of a paradox that Lav Diaz spent the first years of his life in a hamlet with no light bulbs and electricity. His parents were teachers who had left the comforts and opportunities of city life to pioneer in education in the largely undeveloped region of Mindanao. There, they taught their students, adult and child alike, how to cut their nails and brush their teeth… why education was important… that there was a nation called the Philippines and that they were part of it. Diaz’s parents were bookworms and infected him with their love for literature, especially Russian, above all, Dostoyevsky, whose Crime and Punishment and lost souls searching for redemption would later directly inspire Diaz’s first feature-length film, Serafin Geronimo: The Criminal of Barrio Concepcion (1998) and some fifteen years later, Norte, the End of History. The melancholy and solitude of growing up in a remote hamlet, unencumbered by electronic media, gave Diaz an appreciation of nature’s preternatural beauty in its Philippine aspect, something he would express in myriad visual odes in films like Norte. The poverty of the villagers living in the midst of nature’s bounty left an imprint on Diaz and led him to search for the roots of such tragedy, finding links to the systemic governmental corruption that had long plagued the country, then under the rule of Ferdinand Marcos. Two hours away over rough roads from their hamlet was a town center with four movie houses showing double-bills and it became a practice of Diaz’s father, a “cinephiliac” per Diaz’s own description, to take his four children every weekend to watch all eight movies on show, with the family often sleeping in the bus station to save on funds. Apart from the stray art house bird like Aguirre, the Wrath of God, the offerings were for the most part Philippine and Hollywood commercial fare, in a mode of filmmaking that Diaz would eschew in his mature years as a director, yet those films would forever mark the beginnings of Diaz’s love affair with cinema. Later, as part of a school project, he was assigned to watch Lino Brocka’s Manila in the Claws of Light (1975). Moved by the film’s power, Diaz decided to become a filmmaker. Religious and social strife involving Muslim and Christian inhabitants that spilled over to bloodshed and escalated into indiscriminate bombing by the military forced the family to resettle in a nearby province. It was during this period that Diaz witnessed some of the worst excesses of Martial Law imposed by President Marcos, including military zoning, torture and mass killing. The experiences of this regime would emerge time and again in his stories, yet however specific his refractions of Martial Law themes, Diaz would often find a way to expand these into universal examinations of fascism, collective memory, idealism, the persistence of human suffering, and the search for truth and redemption. A case in point is Norte. At a Q&A following the film’s screening at the New York Film Festival, Diaz stated that the character of Fabian was inspired by that of Ferdinand Marcos, in his youth a brilliant lawyer convicted of murdering a political opponent but whose self-defense and maneuvering led to a Supreme Court exoneration. Asked about the meaning of the film’s title, Diaz said that Norte referred to the film’s location, Ilocos Norte, Marcos’ home province, and that the rest of the title was a protest against attempts by some quarters in the Philippines to whitewash the history of Martial Law years and in effect “end history.” And for Diaz, truth is paramount, as he believes that cleansing and recovery cannot begin from falsehood. In any case, Norte’s reach is such that audiences and critics around the world, whether or not they knew anything substantial about the country’s recent history, have resonated in personal and profound ways with the film’s exploration of evil unpunished and its characters struggling to find respite and redemption in a seemingly meaningless universe. In Norte (co-written by Diaz and Rody Vera), Dostoyevsky’s Raskolnikov finds a modern reincarnation in Fabian (Sid Lucero) who, to the dismay of his former professors and classmates, has dropped out of law studies, thereby depriving the school of a potential front-runner at the bar exams. The first scene, an extended chat in an airy restaurant among Fabian and professors (Moira Lang, Perry Dizon) careens in topic from Fabian’s dropping out, to post-modernism, present-day morality, anti-existentialism and insomnia, with a droll, youthful spirit that makes similar scenes in French New Wave films still bracing to this day. The know-it-all Fabian faults the others for their incapacity to budge beyond mere words and sophistry in the face of evils besieging humanity, while he himself is quite ready to put theory into practice. As Raskolnikov did, he eventually acts on his convictions by killing the nasty, usurious town moneylender Magda (Mae Paner). The blame soon falls on a poor villager and client of Magda’s, Joaquin (Archie Alemania), who was involved in a previous altercation with the moneylender regarding an heirloom necklace pawned to her by Joaquin’s wife Eliza (Angeli Bayani). Guilt sends the middle-class Fabian into an extended bender, his sometimes operatic sequences interlaced with stoic scenes of Joaquin and Eliza, one struggling to survive the brutality of prison life, the other caught in a cage of poverty as she pushes vegetable cart around town to support the family. In its depiction of Joaquin and Eliza’s struggles, Norte is a powerful indictment of the country’s national dysfunction that underlies the poverty of so many of its citizens. Yet as New York Times critic AO Scott wrote, Norte is not a “document of despair.” Instead, “like any true work of art, its very existence is an exhilarating triumph over complacency.” Despite the hopelessness and haplessness gripping not only Joaquin’s family but, in a very different middle-class way, Fabian’s as well, various of the film’s elements account for the feeling of exhilaration that Norte elicits:

Diaz formally began his film career in the late 1990s doing low-budget studio-financed films (most memorably Serafin Geronimo and Naked Under the Moon). His filmography took a quantum leap forward with the astounding masterwork Batang West Side (2002), the story of an investigation into the death of a young immigrant in Jersey City. The first of his independently produced films, he let story, vision and improvisation organically determine the film’s length, and ended up with a running time of five hours. The power, complexity and clarity that the film attained in its appropriate length of time convinced Diaz to produce his future films outside the straitjacket of the commercial movie system. Diaz’s filmmaking soon took a radical direction starting with Evolution of a Filipino Family (2004) -- continuing with Heremias: Book One (2006), Death in the Land of Encantos (2007), Melancholia (2008), Century of Birthing (2011) and Florentina Hubaldo, CTE (2012). Running times, never even a consideration until the final edit, ranged from six to eleven hours per film. He pegged the films’ palette at black-and-white and avoided using time-honored tricks for intensifying and manipulating audience reaction such as musical score, close-up, and montage. He recorded his often improvised scenes with one motionless camera and strung together whole sequences with single wide shots running for minutes on end. He would often linger over a landscape before slowly bringing in the human characters with their burden of strife and torments. Diaz produced these works through times that would have broken a less committed or stubborn artist. Commercial theaters refused to even hear of such long-form films, let alone slow long-form films (perverse!), and Diaz could only finance his work through loans from friends (most of all the writer Alexis Tioseco) and the occasional handout from a Hubert Bals Fund, Göteborg Fund or Guggenheim fellowship. Even for his most ardent supporters, Diaz’s films can pose daunting challenges, requiring commitment not usually accorded the film medium with its customary role as entertainment and escape. However, patience and persistence in engaging with a Diaz film are often rewarded by the experience of total immersion in resonant lives, astonishing epiphanies, and a refreshing sense of simple, non-manipulative sharing that feels very much like respect. Norte is a bit of a departure for Diaz in its use of color cinematography, though even here Diaz underexposed the footage while shooting, then desaturated in post-production to approach the pure, if luminous, feel of black-and-white. While the camera has been allowed a bit of movement in Norte, a tracking shot here, a rare close-up there, it remains for the most part a motionless and impartial witness to portentous events. Since Batang West Side, Diaz has had passionate albeit small bases of admirers (exponentially expanded after Norte) in the festival circuit where he is mentioned alongside masters of contemporary contemplative cinema like Bela Tarr, Nuri Bilge Ceylan and Tsai Ming Liang; and awarded with his own menagerie of trophies from the Orizzonti Grand Prize at the Venice Film Festival (Melancholia, 2008) to the Golden Leopard at Locarno (From What Is Before, 2014). To date, Norte is Diaz’s most acclaimed and widely distributed work. After causing a sensation at its world premiere at Cannes, it became Diaz’s most invited film in the festival circuit, figured among the ten best films in the annual British Film Institute int’l critics poll, and led to major Lav Diaz retrospectives in Sâo Paulo and at the Film Society of Lincoln Center. Norte stands out with a limpid style that Diaz has refined through a decade of just forgetting about traditional cinematic practices in order to focus more closely on artistic vision and his own pulse. Despite its disavowal of many time-honored cinematic conventions, Norte nevertheless displays the classic attributes that make for great cinema: Unerring eye for composition, ability to retain suspense, the capacity for surprise, and characters like Fabian, Eliza and Joaquin who continue to haunt the soul’s eye long after their light has vanished from the screen. blog comments powered by Disqus |