| IN EXTREMIS

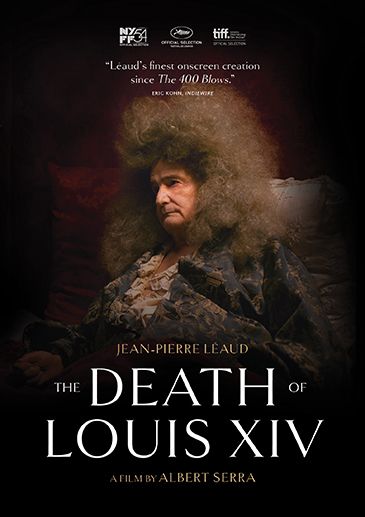

an essay by jordan cronk Following a brief introduction in which the Sun King is wheeled through the Gardens of Versailles by a pair of humble valets, the film casually moves inside the palace walls for the remainder of its runtime. When we next meet our aging protagonist, mostly bedridden and surrounded by a cabinet of servants and confidants, he’s awaiting the arrival of a crack medical team from the Sorbonne, beckoned on his behalf by his personal physician Dr. Fagon (Patrick d'Assumçao). The King will be dead in less than 24 days, from cardiac arrhythmia and the ruthless spread of gangrene in his left leg. While visitors and well-wishers look on from an adjacent room and underlings plead at his bedside for increased military resources, Louis lay mostly comatose, mumbling instructions and gingerly moving only to kiss his pet Borzoi hounds. Serra and cinematographer Jonathan Ricquebourg film the King’s slow death with an equally marked patience, in a time-based style that’s become something of a trademark for the director. In this meticulously rendered world, every action, every movement, every word takes on an increased gravitas; even the King’s afternoon spoonful of soft boiled egg is heartily applauded for the effort it takes to bring the utensil toward his magnificently coiffed head. (“Bravo, sire,” the chorus praises.) Much of The Death of Louis XIV’s power comes from the intertextual dynamic between the historical specificities of the narrative (assembled by Serra and co-writer Thierry Lounas from the memoirs of Saint-Simon) and the meta-cinematic connotations of its casting. Though Serra claims to have had little interest in Léaud’s past as an actor, there’s no denying the associations conjured by the mere presence of a performer of Léaud’s stature––to say nothing of age (he was 71-years-old at the time of filming)––in the role of a dying patriarch. As arguably the most iconic French actor of his generation, Léaud brings an entire lineage of European cinema, one already threatened by the passing of time and indifferent audiences, to bear on a narrative predicated on fate and the relinquishing of past glories. (In the film’s most moving scene, the King is seen instructing his adolescent heir to remain morally upright and to one day make peace with his neighbors.) Utilizing stationary camera setups, often framed in detailed closeup, Serra methodically documents the aura of a man whose life has been almost entirely lived and recorded through cinema. When the film climaxes with an extended shot (accompanied by the anachronistic use of Mozart’s Great Mass in C Minor) of Léaud looking directly into the camera, one can’t help but call to mind any number of the actor’s most memorable onscreen moments––perhaps none more obvious than the epochal freeze frame that closes François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows (1959), an image of a 14-year-old Léaud that single-handedly announced the arrival of a new generation of film artists. When I interviewed Serra following the film’s premiere at Cannes he explained that one of the intentions behind the project was “the idea of living the present through the past,” rather than “living the past through memory.” If the latter is how one might classify Serra’s uniquely bastardized interpretations of the (non-)adventures of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza (in Honor of the Knights, 2006), the legend of the Three Kings (Birdsong, 2008), and the entwined histories of Casanova and Dracula (Story of My Death)––each hinging to various degrees on myth, memory, and received wisdom––then it’s logical to view The Death of Louis XIV as a work of cinematic and historical reciprocity set at a watershed moment of cultural and scientific enlightenment, just as the present was being pushed stubbornly toward modernity on the winds of triumph and tragedy alike. And in that sense the film is a work of classical modernism to stand alongside the likes of not only Rossellini’s own The Taking of Power by Louis XIV (1966), but also the literary adaptations of Éric Rohmer (Perceval le Gallois, 1978; The Lady and the Duke, 2001), Jacques Rivette (The Duchess of Langeais, 2007), and any number of works by Manoel de Oliveira (Doomed Love, 1978; Francisca, 1981; et al). Along with the increasingly deft temporal consolidations of his narratives, Serra’s films have simultaneously undergone a more dramatic locational shift from exclusively outdoor backdrops to largely interior settings. If The Death of Louis XIV completes the transition, it does so in tandem with the refinement of a formal arsenal that’s become ever more efficient in its spatial and compositional maneuvers. The King’s cramped bedchamber is sketched in medium shots that linger just long enough to take in the full spectrum of plush furnishings and reflective surfaces that render the space a sanctum of living history, while closeups in turn map this history onto the weathered faces of those gathered in collective mourning. The director’s aesthetic palette has likewise grown richer as a result of a more controlled working environment. As one of the foremost artists exploring the extremes of digital cinematography, Serra’s preference for long takes and natural light here achieve a previously untapped grandeur, as the soft, tactile, ephemeral textures of his imagery act as an aesthetic analogue to the life fading before his lens. Despite the fragile, intimate atmosphere, it’s an approach that still allows for the odd poetic gesture and occasional breach in the film’s facade. Indeed, just as Léaud had previously paused as if frozen by the camera’s gaze, so too does the film end with Fagon addressing the viewer, following the King’s grisly disembowelment, with a humble pledge to do better next time. Suddenly, the irony of Serra’s most devout film feels less prescribed than poetically ordained. Here’s to the future. --- Jordan Cronk is a critic and programmer based in Los Angeles. He runs Acropolis Cinema, a screening series for experimental and undistributed films, and is co-director of the Locarno in Los Angeles film festival. He's a regular contributor to Cinema Scope, Film Comment, and Sight & Sound. blog comments powered by Disqus |