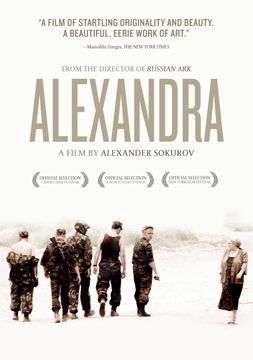

| GRANDMOTHER COURAGE:

INDOMITABLE OPERA DIVA TAKES ON SOKUROV'S ALEXANDRA an essay by david shengold Sokurov's two latest films, the documentary Elegy of Life: Rostropovich, Vishnevskaya (2006) and feature Alexandra (2007) also showcase an icon of Russian musical high culture -- indeed, of Soviet cultural history. Galina Pavlovna Vishnevskaya (1926-2012) represents a monument of a different sort: the exiled, retired and returned prima donna assoluta of Moscow's legendary Bolshoi Opera. But she is also a native Leningrader who barely survived the wartime Nazi blockade to begin her ascent to artistic greatness and world fame singing operetta in her early teens. After Vishnevskaya and her husband, the legendary cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, were stripped of their Soviet citizenship while abroad in 1975 for having provided refuge to the towering anti-Soviet chronicler and author Alexander Solzhenitsyn, they continued their musical and recording activities. Sopranos have fewer opportunities (and shorter career prospects) then cellist-conductors. Eventually, in 1984 -- while still performing concerts and raising two daughters -- Vishnevskaya found time to pen a memoir, titled Galina. Unlike all other prima donna memoirs, her volume does far more than settle scores with rivals (although some of that goes on) and report artistic triumphs -- though those triumphs included fruitful working relationships with two of the great composers of her time (Shostakovich and Britten) and acclaimed performances not only on her home country's leading stages and concert platforms but those of Milan, Paris, Vienna, New York and San Francisco. Beyond all that, Vishnevskaya's book is a stark account of the difficulties she faced in growing up and working in the Soviet system. Not only poverty, a broken family life and the turmoil and starvation caused by the 1941 German invasion and siege of her native Leningrad are detailed; she names names, outlines betrayals, and in harrowing detail describes the corruption, blackmail, extortion and justified fears to which Soviet artists (and others citizens) were subject. Of course, in Soviet times, she and Rostropovich -- once acknowledged as among the artistic elite and given many privileges and awards -- became "non-persons" once in exile: their recordings vanished; books and photos were altered to obscure their having participated in premieres. Prints of the famous 1958 studio film Roman Tikhomirov made of Tchaikovsky's opera Eugene Onegin, which paired the lovely Ariadna Shengelaya with Vishneveskaya's radiant young voice in one of her most famous parts had the frame bearing the soprano's name cut out of them. Precipitous transfers of old tapes to DVD perpetuated this error. Vishnevskaya retired from singing staged opera in 1982, in a final Eugene Onegin done in Paris; in the following decade she sang concerts and tried her hand at stage direction. Eventually, when the Wall fell and the Soviet Union disappeared, she and Rostropovich returned, first as honored guests and eventually as participants in cultural life. They returned many Russian art objects gathered around the world to public view in Moscow. In 2002 Vishnevskaya opened a school for singers' training, with an attached theatre for performance. She has continued to take an active -- sometimes polemical -- part in the operatic life of the Russian capital. Sokurov, born in Southern Siberia, comes from a military family; among his output are three (of a projected four) films treating the lives of major military actants of the twentieth century: Lenin, Hitler and Hirohito. In Alexandra we see no one whose decisions impact large populations: merely a number of isolated officers and soldiers, a number of civilians in the Chechnya-like area they are occupying -- plus one visitor whose advent astonishes everyone with whom she comes into conduct: an octogenarian grandmother arrived from somewhere in faraway Central Russia to do a personal inspection tour of her army officer grandson's life and well-being. Alexandra is not Galina Vishnevskaya's feature debut. In Mikhail Shapiro's 1966 film of Shostakovich's harrowing opera Katerina Ismailova (now in DVD release), working alongside film actors, she alone does her own singing-- not to mention stunts involving long immersions in freezing waters. Beyond her amazingly characterful singing, her dramatic performance is spectacular. Her work for Sokurov in Alexandra surely marks the most moving non-singing cinematic characterization by a famous opera singer since Czech soprano Jarmila Novotná's displaced postwar mother in The Search (1948). Widowed, the forthright older woman Vishnevskaya plays has traveled far under difficult conditions to visit her grandson Denis at the front (footage filmed in Grozny, the Chechen capital). Denis -- a rangy, taut killing machine (and self-described ladykiller) well embodied by Vasily Shevtsov, seems to her a mystery. Why isn't he married at age twenty-eight? Why doesn't he read? What does he know how to do but kill? At times the images and cinematography seem to convey a kind of stylized eroticism in their relationship -- and indeed in the way all of the affection-starved, decontextualized young soldiers stare at Alexandra, as if at some mythic amalgam of Russian wife and mother. Though Vishnevskaya's performance is devoid of vanity, her clothes simple and old-fashioned and her face free of evident make-up, she remains a very handsome woman capable of a powerfully searching gaze. Alexandra's manifest moral and physical strength contrasts with her recurrent exhaustion and occasional moments of seeming befuddlement. (In actuality not a tall woman, Vishnevskaya learned for her operatic roles how to project an intensity and presence that makes it difficult to take one's eyes off of her.) This combination of attributes holds her in good stead whether she accidentally strolls through an unlit mine field or takes an unauthorized off-trip base to the local market in a nearby devastated town. Though the film shows no bloodshed whatsoever, Sokurov always allows the potential for violence (including kidnapping) to brew. The resentful attitudes of the village youth and men contrast with those of Malika (Raisa Gichaeva), a former Chechen teacher-- itself a flag of a certain Soviet code of shared humanism, and her largely ruined apartment has the Russian books to substantiate this -- who hosts the exhausted Alexandra. Their briefly etched bond resonates with their common destiny -- Alexandra is of the long-suffering generation of the "Great Patriotic War," as Soviet historiography termed World war II -- as witnesses to strife and loss. Alexander Burov's striking cinematography keeps the visual palate of the military world stark and washed-out; Alexandra herself, and the largely feminine sphere of the market, provide colorful contrast. Alexandra premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 2007; it subsequently won release at art house cinemas across North America. Part of Sokurov's growing corpus of important cinema, it also will stand as a monument to the indomitable artistic courage of Galina Vishnevskaya. ----- David Shengold has written for Playbill, Opera News, Opera (UK),Opéra Magazine (France), Slavic Review and Time Out New York among other venues. He has contributed program essays to the Metropolitan, New York City Opera, Covent Garden and Wexford Festival programs and lectured for the Glimmerglass Festival and Philadelphia's Wilma Theatre and several colleges on opera and film. He has taught course on opera, literature, cinema and cultural history at Oberlin, Mount Holyoke and Williams Colleges. |