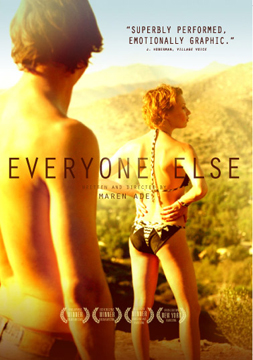

| EVERYONE ELSE

an essay by mark peranson Though hinting at the type of relationship earlier dissected in Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy (1954, an obvious touchstone given the setting), Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage (1973) (which Ade, her cast, and cameraman Bernhard Keller watched in preparation for the film), or Eustache’s The Mother and the Whore (also 1973), Ade’s second film Everyone Else (Alle Anderen) is a new kind of drama about the things some do for love, and I don’t use the word “new” casually. (You might also recall that classic Billy Joel line, “Don’t go changing to try and please me.”) Also a winner of a Silver Bear, the runner-up Grand Jury Prize, Everyone Else became the first representative of the new generation of the so-called “Berlin School” to merit such a significant award at the Berlinale, even if with its pointed and carefully scripted dialogues Ade’s talky film perhaps stands only tangentially next to the work of Christian Petzold, Thomas Arslan, Angela Schanelec et al. (It perhaps most resembles, in structure, the films of Ulrich Köhler, Ade’s current partner, who helped advise on the script.) Everyone Else is a film where constant shifts in point of view are subtle and never clearly indicated; just when you think you’ve grasped the film, it slips away, yet again, like grains of sand through your fingers. I’ve seen the film four times, and each viewing has left me even more uncertain of what I’m supposed to think at any one moment, or about Chris and Gitti’s relationship as a whole: this creates a different kind of experience for a viewer than the one posed by such a normally conventional type of cinema (the romantic drama or love story), a film at times psychological, at times theatrical and/or childish, at all times, realistic and honest. (A huge part of the credit must go to Eidinger and Minichmayr, breaking through in their first major film roles; both are trained theatre actors, Eidinger is notable as being one of the directors of the Schaubune theatre in West Berlin, one of the city’s most radical theatre troupes.) Perhaps the questions asked by Everyone Else, which digs a knife deep into the flesh of a nascent relationship without falling into dramatic conventions—and at the same time portrays a social class with an unflinching acumen—are so challenging that the only way to deal with them is by, as Variety’s Derek Elley did in his downright stupid Berlinale review, dispensing with them entirely. (“Simply fuzzy filmmaking of the worst sort.”) Fuzzy, my ass. Perhaps one can say that the first half of the film is more aligned with Chris, and the second with Gitti, but Ade, her actors, and Keller’s camerawork, provide more subtle distinctions within this structure, and, consequently, do away with the traditional definitions of masculinity and femininity read on the film’s surface. Isolated at Chris’ parents summer house, surrounded by the material evidence (in the form of hopeless kitsch) of a previous generation’s way of living, they first withdraw to separate spaces, and mimic the roles of their elders: he to the father’s room, and she to Chris’ mother’s. (“The house does something to them,” Ade told me, befitting a film that at times threatens to twist into horror territory.) Set in her home town of Karlsruhe, Ade’s more conventionally perceptible and aggressively focused debut, The Forest for the Trees (2003)—a film about Melanie, a young teacher who essentially starts stalking a woman she just wants to be friends with—acts as a sly and just as uncomfortable comment on the way women are often depicted and defined as unstable. This unpacking continues here as Gitti’s “female” emotions take more and more hold of her as the film develops, culminating in acts that can be read, if you’re thinking in a traditional framework, as full-blown psychosis. (Or, to be kinder, a desperate act of an egocentric person.) Though instability keeps being hinted at by Ade and her actors—perhaps best symbolized in a scene where Chris bangs into a glass door and knocks himself bloody and senseless, though not quite unconscious—the break in the film comes in a chance meeting. In a supermarket, Chris and Gitti are confronted by a more successful and ideal version of themselves, in the form of freshly minted documenta artist Hans (Hans-Jochen Wagner), who reeks of superiority, and his pregnant wife, Sana (Nicole Marishka). Hans’ presence has the impact of transforming Chris, who is awaiting the results of an important architectural competition, exacerbating his latent asshole tendencies. In reaction, Gitti, who, as in the best of Greek melodrama, grabs for the knife. (It perhaps does not come as a huge surprise that Ade chose to give Chris the profession of architect because of the job’s similarities to being a filmmaker.) This shift in the third act of Everyone Else drew some flippant criticism after its Berlin premiere as going off the rails, a comment that only makes sense to me if one doesn’t pay close attention to the first half (especially a discussion about Batman, or to the way Chris and Gitti are both lying to themselves and to each other), or is trapped in a way of perceiving glues to classical forms, such as the art that Ingrid Bergman surveys during her own fraught Italian vacation. Ade has said that the four characters combine in her mind to create a single person, and that makes some sense to me, because in a way the philosophical equivalent of the film is Plato’s classic work on love, the Symposium; perhaps Ade’s film leaves us with Socrates’ ultimate plea that “love is beggardly, harsh, and a master of deception…but also delicately balanced and resourceful.” The magic of Everyone Else—and there is something magical about it—is hard to define or pin down, right up to the ambiguous ending, and that’s exactly what makes it a great film: you can’t summarize it. (And if that’s fuzzy, I’ll take fuzzy any day of the week.) Watching (and rewatching) it yields an ineffable sense that the complex emotions are being created for the camera are themselves beyond the complete intentions of the actors and the director; this in no way is to slight the two amazing performances, or Ade’s precise direction, only to say that in the best art, always by its nature a product of human fallibility, the final product tends to be part conscious, part unconscious.

|