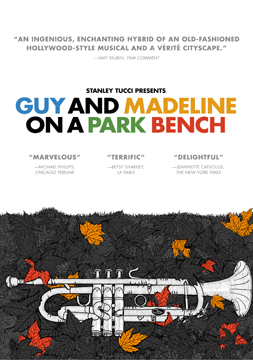

| GUY AND MADELINE ON A PARK BENCH

an essay by amy taubin Set largely within Boston's famed but economically precarious jazz community, the film is a desultory version of the classic romantic meet cute/breakup/reunite narrative. Here a boy named Guy (Jason Palmer) meets a girl named Madeline (Desiree Garcia), dumps her for another, realizes he misses her and pursues her again. Whether she'll welcome him back or not is far from certain. The opening credit sequence is a cliff-notes version of Guy and Madeline's brief romance - park bench first kiss to park bench kiss-off in 2 1/2 minutes. Then, as if the movie were a recording session where the bandleader says "let's take the ending again, but more leisurely," Chazelle doubles back to the last week of the relationship, showing us how, by chance, Guy, in the steamiest subway encounter since Samuel Fuller's Pickup on South Street (1953), hooks up with Elena (Sandha Khin), takes her to his apartment, and, thinking he prefers this new, seemingly self-confident young woman, tells the pensive Madeline that it's over. (We never hear him say those words; whenever possible, Chazelle relies on facial expressions, gestures, and, at peak emotional moments, songs, to carry meaning - thus distinguishing his filmmaking from that of his so-called "Mumblecore" peers.) The elliptical narrative continues to follow Guy and Madeline as they go their separate ways. For a short while, it also follows Elena, who leaves Guy as soon as she discovers he's more involved with his trumpet and his fellow band members than he is with her. Madeline, however, continues to carry a torch for Guy even after she takes a trip to New York and has a fling with an older man (Bernard Chazelle, the director's father). A student at Harvard when he started Guy and Madeline, Chazelle took time off to finish it, then went back for his degree. Harvard is one of the last remaining film departments where students shoot and edit in 16mm. Chazelle, who, in addition to directing, scripting, and writing the lyrics for Guy and Madeline, is the uncredited cinematographer and editor, decided to use the same kind of 16mm camera for his debut feature that he employed for his student documentaries. Guy and Madeline thus combines the look of 1930s Hollywood musicals, albeit more homespun, with cinema verite - as if Dudley Murphy's short musical Black and Tan (1929) starring Duke Ellington and his band was merged with Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin's Chronicle of a Summer (1961). Just as French New Wave directors referenced the movies they loved, Chazelle borrows from his favorites: John Cassavetes' Shadows (1959), Chantal Akerman's The Golden Eighties (1985), Jacques Demy's The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964), and that's just the short list. Chazelle uses his cinephiliac's passion for French New Wave and American pre-Sixties movies to explore the particular, contemporary American milieu to which he belongs - the Boston bohemia centered around music schools and universities. In terms of romance, this milieu is nearly colorblind, and was so even before "the Obama moment" brought the best and worst of race relations to the surface. When it comes to art, however, it's a different story. The titular Guy is as exclusively dedicated to some of the giants of black music (Clifford Brown, John Coltrane, Grandmaster Flash) as Chazelle, who was raised in both Paris and the East Coast of the U.S, is to French and American movies. Just as it synthesizes cinema verite with the highly artificial genre of the musical, Guy and Madeline melds big band swing (Justin Hurwitz's infectious score was recorded for the film by the Bratislava Symphony Orchestra) with small ensemble progressive jazz. Palmer is, in real life, one of the rising stars of Boston jazz, so the scenes where Guy rehearses or performs are at once documentary and fiction. The first of the film's two big musical numbers is staged in a Boston music landmark, Wally's Jazz Cafe, which is so tiny that most of the time the camera can't fit in the room. The musicians jam and a couple of tap dancers erupt into motion, as Chazelle's handheld camera, stuck in a hallway, pans back and forth between two doorways, like a latecomer craning for a better view. The repetitive camera movement lays down its own improvised beat for the scene, kinetically attuned to both the music and the dance. In high school, Chazelle was a prize winning percussionist, and his sense of rhythm and syncopation informs his camerawork and editing. A mix of skill and spontaneity is at work in every aspect of his filmmaking, but particularly in his editing which, first to last, is astonishing. One of the great pleasures of the DVD is that it affords one the opportunity to savor how Chazelle puts shots together: the montage of close-ups in the two extremely sexy (but in no way explicit) scenes between Guy and Elena - the first in the subway laced with promise, the second in the shower edged with discontent; the match cutting on faces; the way time seems to fall apart in the transition from ordinary life to the song and dance numbers. It's a rare director who is as accomplished in the hands-on aspects of filmmaking as in structuring a story and in casting and working with actors. The entire non-professional cast brings emotional authenticity and enthusiasm to the screen. Palmer has the mystery and wattage that could spell stardom. Garcia's Madeline is defined by myriad shades of ambivalence and uncertainty, but in her break out dance number, when she discovers that she might not have lost Guy after all, she miraculously seems to levitate while remaining in her adorably earthbound body. Just when she least expects it, she's overcome with pure joy. Guy and Madeline has had a similar effect on audiences. Enjoy it and root for Chazelle to make another, ASAP ----- Amy Taubin is a contributing editor for Film Comment and Sight and Sound magazines and a frequent contributor to Art Forum. She is the author of Taxi Driver in the BFI’s Film Classics series. Her critical essays are included in many collections. From 1987 and to 2001 she was a film critic for the Village Voice where she also wrote a pioneering column about independent film titled Art and Industry. She teaches at the School of Visual Arts in NYC. |