| LATE OLIVIERA

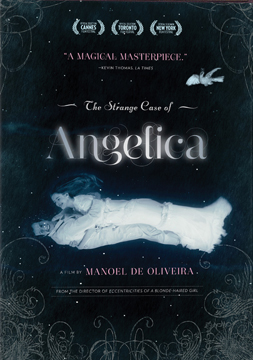

an essay by haden guest The extraordinary Portuguese filmmaker Manoel de Oliveira is an important exception to the tradition of the late film as poignant emblem of career obsolescence. Vitally active at the tender age of 102, Oliveira defies this still dominant auteurist paradigm and, seemingly, human biology itself through his remarkable late career productivity and through his notable turn away from the expected trajectory towards stylistic overstatement. Indeed, Oliveira’s recent films introduce a new sparseness and enigmatic lucidity into his oeuvre, a restraint and unspoken mystery exemplified by the lapidary and fable-like Porto of My Childhood (2001), I’m Going Home (2001), Belle Toujours (2007), Eccentricities of a Blond Hair Girl (2009) and The Strange Case of Angelica (2010). Further distinguished by a strong thematic and stylistic unity, these late films together share an abiding fascination with the past and with a kind of temporal paradox that reveals “lateness” itself as one of Oliveira’s grand themes. Of course, the very term late signifies something quite different when applied to the work of an artist whose unusually long career is distinguished by the steady productivity of Oliveira’s past thirty years. In Oliveira’s case, however, late also takes on special meaning when one recalls that his first steps as a filmmaker were guided by an unusual delay—by the lateness of the struggling Portuguese film industry in adapting to sound which allowed him to make the silent film Douro, Faina Fluvial as his 1931 directorial debut. Yet a longer, more troubling delay would exert a shaping influence on Oliveira’s cinema beginning with the commercial failure of Aniki Bobo (1942) and followed by the blacklisting soon after by the repressive Salazar dictatorship which left Oliveira unable to realize all but the occasional short film and his pioneering documentary Rite of Spring (1962)—a creative limbo state essentially unbroken until The Past and the Present (1971), the first entry in his so-called “Tetralogy of Frustrated Love”. This long period of near silence left cherished projects suspended indefinitely—among them Oliveira’s latest feature The Strange Case of Angelica, a dream burnished by Oliveira for over fifty years and made real at last only in 2010—thus becoming a late film in a sort of double sense. Looking back over the early part of Oliveira’s interrupted career, certain of his first films emerge as signposts pointing assertively towards directions subsequently abandoned—towards the Soviet-style montage refined by Douro and the radical documentary short O Pao (1959) for example, and towards the protoneorealism explored in Aniki-Bobo. Instantly mastering and leaping past major currents of European cinema, these films together defined an important and lasting dimension of Oliveira’s cinema- its singular ability to remain deliberately out-of-step with, and somehow always far beyond, dominant trends and tendencies. The asynchronous quality so essential to Oliveira’s films was pushed even further by his absence from the efflorescence of postwar European art cinema of the 1950s and 1960s. When he began once again to direct features, Oliveira remained notably unaffiliated with any established school or movement, turning instead with remarkable fixity to literature, theater and history for his primary inspiration. Boldly adapting such formidable canonical works as Camilo Castelo Branco’s celebrated 1862 novel Doomed Love and Paul Claudel’s epic 1931 play The Satin Slipper into lyrical yet purposefully monumental films—each monumentally long at four and seven hours, respectively—Oliveira effectively argued for an earned equivalency between literature, theater and the cinema. Making innovative use of such devices as multi-layered voiceover narration and overtly theatrical, tableaustyle mise-en-scene, Oliveira’s work since his famous Tetralogy has maintained an unhurried indifference to the urgencies of the various post-WWII new waves and new cinemas, drawing inventively from the deepest literary and theatrical pre-histories of narrative cinema. The frequently enigmatic and seemingly tenuous connection of Oliveira’s films to their present moment has grown even more pronounced in his recent work which increasingly takes the past as its very subject. An important expression of this tendency is Oliveira’s frequent turn to the autobiographical, an impulse first and arguably best expressed in Voyage to the Beginning of the World (1997). Following the nostalgic road trip of an aging Portuguese filmmaker pointedly named Manoel, Voyage is structured around an episodic series of visits to sites of his youth, united by extended and hypnotic shots literalizing the dominant perspective of Oliveira’s late films, aimed backwards through the rear window to capture the road ribboning away into the distance. In both Voyage as well as the lovely featurette Porto of My Childhood, Oliveira openly embraces the cinema as a type of fragile aide-memoire, a means to transform the eccentric, unreliable fragments of personal memories into an imaginary narrative. Just such a notion of the past as the realm of the imaginary also guides the provocative exploration of deep rooted Portuguese national myth in Christopher Columbus: The Enigma (2007) and The Fifth Empire: Yesterday as Today (2004) which each offer speculative, hypothetical and polemical rewritings of history—arguing, for example, that Columbus was in fact Portuguese born and that the controversial 16th century Portuguese King Sebastian was a visionary hero. For Oliveira, history, like memory, is ultimately a mode of fictional narrative complementary and comparable to the story-telling searching at the heart of the cinema’s often uncertain art. Interweaving myth and memory, Oliveira’s recent films unfold a series of profound metaphors for the cinema’s always poetic relationship to a past that can never be “captured” by film in any traditional realist sense but only distilled into a fleeting and often mysterious essence of images. With The Strange Case of Angelica Oliveira delivers his most direct statement on the cinema itself, offering a meditation on the promise and limits of film as both an artistic and temporal medium. Pointedly reminding us of the cinema’s photographic origins, The Strange Case of Angelica examines film’s inherent power to conjure a bewitching illusion of the past come alive, the dead resurrected. In this way the young photographer becomes an obvious stand-in for the filmmaker and the dead maiden a figure for the magic and melancholy of the cinema’s relation to a world whose always receding past remains elusive, always too late. Juxtapositioning the photographer’s frustrated Lumière attempt to portray the rocky soil of labor with the sublime Méliès dream scenes of his reunion with Angelica, Oliveira’s latest film embraces a vision of the cinema as a fragile balance between realism and illusionism, between the fugitive world of the present and the fantasy resurrection of the past. As 21st century proclamations continue to be made declaring the death of the cinema, or its rebirth in some digital or virtual form, The Strange Case of Angelica, and Oliveira’s long career in general, suggest that the secrets to the cinema’s unchartered future may paradoxically lie in its storied yet all too often forgotten past. ----- Haden Guest is director of the Harvard Film Archive and lecturer in Harvard's Department of Visual and Environmental Studies. blog comments powered by Disqus |