| THE DRAGON HAS SPOKEN

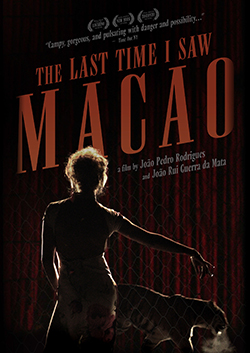

an essay by james quandt Everybody’s looking for something." – Jane Russell in Macao The Last Time I Saw Macao begins as another of João Pedro Rodrigues’ erotic nocturnes, in a darkness that recalls the impenetrable nightscapes of his first feature O Fantasma, his tale of a gay Lisbon garbage collector on the prowl for both refuse and sex. The narrator of The Last Time, the film’s co-director and Rodrigues’ longtime partner João Rui Guerra da Mata, is also on a quest through a shadowy urban terrain, on a rescue mission to save his old friend Candy, who has become the target of a Zodiac cult in Macao. The obscurity in The Last Time, however, is as metaphoric as it is literal: the city ends enshrouded in mist and smoke, much as the narrator spends the film adrift in a miasma of memory. In the provisional precincts of both Macao and The Last Time, all dissolves into uncertainty. In this city of cul-de-sacs and hideous casinos Guerra da Mata is warned that “nothing is what it seems,” and indeed, in a film of false starts and unclear allegiances, little turns out to be as it first appears. Accoutered with two enigmatic preludes, the film keeps shifting genre and register within its strictly controlled monotone, conflating not only fiction and documentary but also what seem half a dozen sub-types of each: conspiracy thriller, neo-noir, city symphony, travelogue, apocalyptic sci-fi, autobiography, essay film, experimental home movie, meta-memorial, and cultural critique. Running a scant eighty-five minutes, The Last Time I Saw Macao achieves immense density through this amalgam of genre and its tight braiding of at least three strands of history: personal (Guerra da Mata’s childhood in Macao), political (Macao's four-hundred years as a Portuguese colony before the handover to China in 1999), and cinematic. Opening with a double homage— to Werner Schroeter’s masterpiece The Rose King, shot in Portugal, and to Josef von Sternberg's orientalist adventure, Macao—the film then proceeds to a desultory staging of a gun battle that looks back to the opening military gambit of Rodrigues' To Die Like a Man. Consciously or not, The Last Time invokes countless other films, ranging from Chris Marker’s La Jetée and Sans Soleil (Time's most obvious analogue in both tone and modus) through any number of Hollywood noirs (particularly Kiss Me Deadly), and employs imagery that recalls directors as dissimilar as Apichatong Weerasethakul (synchronized exercisers in a city square) and Michelangelo Antonioni (the portentous post-apocalyptic finale that recollects L'Eclisse). The baroque, paranoid wit of Orson Welles surfaces more than once; the directors evidently remember The Immortal Story, in which Welles recreated Macao in the Spanish town of Chinchón using Chinese waiters from Madrid. Rodrigues and Guerra da Mata thus manage to fashion a labyrinth that suggests both Marker's vortices of time and memory (the film is full of temporal markers: watches, clocks, and countdowns) and Welles' sinister, centerless mazes. If one finds the labyrinth over-contrived, it's best to remember Jane Russell's own counsel in Macao as she snarls at Robert Mitchum, "It's all a matter of taste." The film’s overture, in which Cindy Scrash erratically lip-syncs Jane Russell's rendition of "You Kill Me" from Macao in front of a cage of cavorting tigers (courtesy of Lisbon’s Victor Hugo Cardinali circus), joylessly squeezing the taut drums of her breasts encased by a cheongsam—a camp signifier of eastern "exoticism"— initially seems a trick beginning, but actually introduces many of the film's motifs and meanings, most obviously the character of Candy and the shoes and wig that will comprise her last vestiges on earth. The tigers portend The Last Time's copious, escalating animal imagery—Rodrigues' oeuvre constitutes a bestiary, especially of cats, dogs, and birds—and emphasize the rampant facsimile that turns nature to its opposite in the city: Macao's ubiquitous tigers are all fake and paper, crumpled and upturned in an entropic late montage, before the film’s final imagery suggests that after nuclear mishap the human world cedes to the beasts. The emphasis on performance and mimicry in Candy's act pervades the rest of the movie: Macao decked out in Christmas drag, peopled by a little girl in a Santa costume vamping for the cameras and a Venice-looking, Sinatra-sounding gondolier serenading his canal with a full-throated "Smile"; the Cantonese opera on television that Guerra da Mata attempts to decode as he awaits Candy's phone call; the empty stage at the Jai Alai casino with its glittery curtain. So, too, Candy's transsexuality signals the film's many references to the liminal: its own breached threshold between fiction and documentary and its shifting, shared narration between the two directors’ voices; the hybrid Portuguese-Chinese traces of Macao's colonialist past; the buxom mermaid in the video; and even the sundry nature of the 1952 RKO film so insistently invoked by Rodrigues and Guerra da Mata, which was partly directed by Josef von Sternberg and finished by Nicholas Ray. "I see I’ve left nearly everything unsaid," the doomed Candy scrawls in her farewell letter, and much the same can be said of the film she appears in (or mostly doesn't), a work of absence and emptiness, severe ellipsis and truncation. Rodrigues and Guerra da Mata refuse to reveal much of the characters' bodies after the initial preludes, an abbreviation that is probably not, as many critics have claimed, a deployment of the trademark isolating frames of Robert Bresson (though the directors greatly admire his work). Rather, in its arch mysterioso, the reliance on hands and shadows reads as a playfully exaggerated trope from noir, especially given the film's conspiratorial narrative about the "great ritual of the chosen ones" that looks back to The Big Sleep and The Lady from Shanghai in its twisty inscrutability, and the cloaked birdcage modeled on the mysterious nuclear whatzit in Kiss Me Deadly. However, like Bresson and his countless copiers, the directors rely on an implicative sound design to insinuate all that we cannot see, including Candy’s murder. What the directors do show in a succession of glorious Marker-like static shots of Macao (and other Chinese sites cobbled to make a more "exotic" locale), employing grates and grilles to replace the scrims and screens synonymous with von Sternberg, reveals a keen eye for symmetry and kitsch: the spume of sparkles illuminating the gauche fa&cecil;ade of the Grand Lisboa Hotel framed by Guerra da Mata's inn window, with an Ozu-like pair of slippers propped against it; a sienna retrofuturistic double phone booth by the waterfront; the crimson, heavily jeweled talons of Madame Lobo fingering toy wooden animals that represent her cult, her victims, or both; the discarded high heel that becomes a synecdoche for Candy's demise; a latticework of glistening fish in the market. The directors interpolate actual photographs from Guerra da Mata's childhood, mostly fading Polaroids, into their montage—our first view of the Macao bay, for instance—as markers of the intertwined pasts of a person and a place that, three decades after his departure, contains few traces of his former life there. The upside down television in Guerra da Mata's cab suggests an oblivious, topsy turvy world, but off-season Macao emerges in the film more as the Capital of Desuetude, where the past emerges superfluous, disused, or otherpurposed. Rickshaws are now just for tourists and the Portuguese language has quickly disappeared after four centuries of use. The narrator's childhood school has become a collection site for rubbish. The old seawall on Praia Grande Avenue, now land-locked, no longer serves to protect the city from the water and stands lonely and neglected. Guerra da Mata's former home, the Moorish Barracks, has been declared a World Heritage Site by Unesco and the Military Club is now deserted, populated only by the ghosts of former Portuguese officers. (Candy resides on the Travessa de Saudade, an address that translates roughly as Melancholy Way, a jokey reference to the dolorous Portuguese sense of loss and longing, sometimes associated with the decease of the country’s colonies.) Most errant of knights in a city that stymies his every move, the inept narrator proves incapable of saving Candy from her fate. "Candy was dead. She asked me for help and I failed," Guerra da Mata intones in the lugubrious voice that passes for hardboiled in this mock-noir. Why Candy ever implored help from the gormless would-be gumshoe, who repeatedly gets lost, even when his destination is close by, or stuck in traffic, who misses a crucial rendezvous after forgetting his cell phone and can’t manage to elicit directions or evidence from any passersby, counts among the film's manifold (and amusing) mysteries. When Candy counsels the hapless one to save himself from Madame Lobo's henchmen, his hitherto infelicidade suggests he’s wise to hightail it out of Macao for the last time. ----- James Quandt is Senior Programmer at TIFF Cinematheque in Toronto, where he has curated several internationally touring retrospectives, including those dedicated to Naruse, Mizoguchi, Bresson, Imamura, Ichikawa, and, most recently, Oshima. A regular contributor to Artforum Magazine, Quandt has also edited monographs on Robert Bresson, Shohei Imamura, Kon Ichikawa, and Apichatpong Weerasethakul. blog comments powered by Disqus |