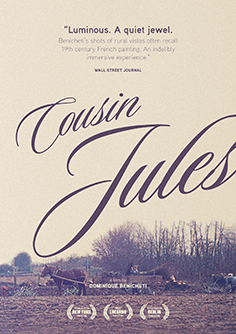

| COUSIN JULES

an essay by haden guest Benicheti's connection to the still vital documentary movement centered around Harvard is deep and actual, grounded in the two years (1974-76) he spent, at the invitation of Robert Gardner, teaching non-fiction film production in the university's Visual and Environmental Studies Department. In his first year Benicheti boldly expanded the existing model course for VES film production into a two semester long collaborative enterprise in which he, as professor, worked side-by-side with his students in the field and in the editing room. The result was an innovative and charged final project entitled Jessica, Look At Me which rhythmically intertwined portraits of three generationally focused Boston-area social institutions; a school for autistic children, a half-way house for troubled teenagers and, directly recalling Cousin Jules, a home for the elderly. In his second year, Benicheti pursued an even more ambitious project; a study of contemporary labor designed for split-screen CinemaScope, but not- as was fashionable at the time- as parallel images with alternating sound tracks. Benicheti's novel and ultimately unrealizable idea was instead for one screen to be an analytic, close-up complement to the other and for the two to be bridged by the same soundtrack. To realize his grand, technologically quixotic ambition, Benicheti rebuilt a 35mm six-plate Steenbeck editing station, attaching a second screen so he could marry the dual image-tracks to the single soundtrack. Although his second collaborative VES film was never realized, Benicheti would remain a year longer at Harvard; not teaching, but busily tinkering in the Physics Department machine shop, working diligently- but in the end futilely- on a sophisticated robot, a true automaton designed to replicate human movement. At the same time, Benicheti's seemingly inexhaustible creative energy was also poured into the realization of his long held dream to study the piano. Benicheti's Harvard interlude offers rare insight into this little discussed and still woefully obscure filmmaker whose magnum opus remains Cousin Jules. His fascination with mechanical bricolage is infectiously apparent in the film's meditative focus upon the atelier workshop of his eponymous cousin, Jules Guiteaux, with Benicheti's extended close-ups of the blacksmith's carefully oiled machines making clear the family resemblance while standing as an emblem and reminder of the complex apparatus deployed to render cinematic the audio-visual dimensions of everyday life. Benicheti's dedication to CinemaScope and true stereo sound would, in fact, have a strong shaping effect upon Cousin Jules, its extreme costs severely limiting the amount of time and footage Benicheti's independent and skeletal production was able to spend. Lack of funding was the reason for the long break in shooting between which gave Cousin Jules its poignant diptych structure built around the off-screen death of Felicie Guiteaux, the farmer's wife. Yet much of the power of Cousin Jules derives from the poetic dialogue that gently bridges its two expressively tempered halves. The hazy mid-summer of the first part is captured in an associational gathering of images of heat- the blacksmith's forge and fire, the flames of the stove, the simmering coffee pot, the steaming soup, the shimmering heat of the sun- quietly absent from the grey early winter of the second part which instead offers images of cold, stillness and solitude that touchingly recall the deceased wife. Benicheti's love of music also informs Cousin Jules' long scenes of blacksmithery and the musique concrete of the hammer's percussive strike, inspiring as well the incredible audio-visual purity of the final shot in the workshop in which Benicheti's camera lingers upon the hammer, thrown down upon the scarred anvil and tottering to a gradual rest with a sonorous song of wood and metal. In the film's mournful second half, the sonic and elemental association of Cousin Jules with tenacious steel is beautifully and literally echoed in the scene where he shaves, in the bracing music captured by Benicheti's attentive microphone of the straight razor drawn neatly across the farmer's cheek. This shaving scene offers a striking example of the subtle poetry by which Benicheti's careful monumentalization of simple gestures and objects upon the wide-screen canvas suggests their ritualistic and sacred dimensions. Avoiding the explicit ceremony of the funeral and mass, Cousin Jules nevertheless reveals the spirituality infusing the everyday of his blacksmith cousin in which all objects seem to have a resolute and total certainty of purpose and place. Simple gestures so artfully framed by Benicheti give the quality of a sacred ceremony to this world of the laconic blacksmith and his wife: such as when he frugally mixes water with wine during the only meal shared by the elderly couple in the film, or, later on, when she solemnly throws into the bright summer air a handful of dust, swept fastidiously from the floor, that poignantly signals the ashes-unto-ashes absolutism of the film's second half. The richly tactile surfaces captured throughout Cousin Jules brings another poetic level to the film. The sculpturally worn crossbar of the well rubbed by the old woman to slow the descent of the bucket, the obdurate anvil pounded by the blacksmith, these weathered objects are themselves offered as a kind of sacred text upon which are written a history of hands and hard, deliberate labor. The beauty and luster of the wood and the steel and their songs without words embody the subtle ways Benicheti's poetic documentary heroizes yet never romanticizes the depth of cyclical time and meaning in the peasant world whose slow disappearance Cousin Jules also movingly predicts. ----- Haden Guest is Director of the Harvard Film Archive and a Senior Lecturer in Harvard's Department of Visual and Environmental Studies. blog comments powered by Disqus |