| WORLD ON A WIRE

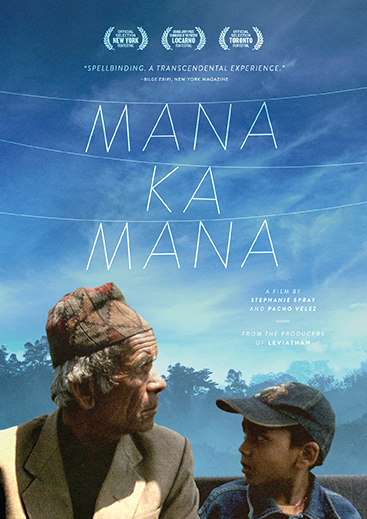

an essay by dennis lim Some, though by no means all, of this information can be gleaned in Stephanie Spray and Pacho Velez's Manakamana. The holy site itself is never glimpsed in the film, which consists entirely of uninterrupted, fixed-camera takes of pilgrims and tourists in the cable car as they ride up or down the mountain, to or from the temple. (The invisible cuts, between rides, happen in the dark of the station dock.) Radically simple in its conception, this mesmerizing film derives its considerable power from its seemingly restrictive formal strategies, specifically from the duration of the shots and the enforced intimacy of the set-up. Each of the 11 sequences, identically framed against a large window that looks out onto the jungle landscape below, lasts for the duration of a one-way ride, which also corresponds to the length of a 400-foot roll of 16-millimeter film. This gives the viewer ample time to observe the travelers - couples, elders, kids, tourists, musicians, and goats - as they contemplate their surroundings, remark on the ride or the purpose of their trip, or simply lose themselves in thought. Each episode documents a journey, stages a self-contained drama, and enacts an encounter - between the subjects and the filmmakers, who are seated opposite though never explicitly acknowledged (Velez operated the camera and Spray recorded sound), and also between the subjects and the viewers, whose experience is likely to parallel that of the passengers on screen, their senses heightened and their minds encouraged to wander. Made under the auspices of Harvard University's Sensory Ethnography Lab (SEL), the increasingly vital incubator of experimental documentary filmmaking responsible for Sweetgrass (2009), Foreign Parts (2010), Leviathan (2012), and People's Park (2013), among other recent examples of form-conscious non-fiction, Manakamana represents a briliantly stripped-down yet surprisingly fruitful synthesis of ethnography and structuralism. Spray, a doctoral candidate in anthropology, has lived and worked extensively in Nepal for years, mostly with families she has come to know well, producing observational works of often breathtaking intimacy; several of the passengers in Manakamana are subjects of her previous films. Shot with the same Aaton camera that the pioneering anthropologist and documentarian Robert Gardner, the founder of Harvard's Film Study Center, used for Forest of Bliss, his film about the holy city of Varanasi, Manakamana grapples with a central question in ethnographic film: how the Other is portrayed. In teasing out a tension between old and new, specifically between the ancient rituals of faith and the conveniences of modern technology, it also addresses a familiar ethnographic theme: a changing way of life. But in keeping with the SEL mandate, Manakamana resists the discursive conventions of visual ethnography in favor of an immediate engagement with the real. The film avoids exposition entirely; all we know of the subjects is what we see and hear as we confront them, head-on and in real time. As much as anything, this airborne version of an Andy Warhol screen test is about the flux of thought as it registers on faces. Manakamana is such a rich experience in part because of how ingeniously it both activates and resolves a host of apparent contradictions. Shot with a camera that is fixed (tripod-mounted to a custom-built platform) but also in constant motion, it is at once a portrait film and a landscape film, an epic in miniature, a documentary predicated on performance. (Velez's background is in political documentary but he gained experience directing theater as a graduate student at CalArts.) The structuring principle and the surreal, high-altitude setting conspire to produce something that is thrillingly mysterious in its effects. The cable car, like cinema, is a kind of time machine, condensing a once grueling trek into a matter of minutes. Slyly evoking the apparatus of cinema - the window acts as a frame within the frame and the passing landscapes recall the illusory scroll of rear projection - the film is itself a self-reflexive rumination on the acts of seeing and listening. (As with most SEL films, the sensory detail emerges in large part from the precision and complexity of the soundscapes, crafted in post-production by the lab's resident sound designer Ernst Karel, who also created the sound piece, derived from audio recordings at the temple, that functions as a mid-movie interlude over a black screen.) For all its rigor, Manakamana doesn't adhere to a predictable or overly strict schema. It's no surprise to learn that Spray and Velez, who recorded 35 rides in all, took well over a year to edit the film, experimenting with countless permutations to arrive at the end result. Manakamana, which shows us six consecutive rides up the mountain followed by five down, is attuned to the rhythms and tonal shifts within and across the episodes. Repetitive structure notwithstanding, the film cycles through a playful variety of registers, from comedy to suspense to psychological drama. Like the best structural films, Manakamana is a kind of head movie, one the viewer is invited to complete. Working within the confines of a 5-by-5-foot glass-and-metal box, Spray and Velez have made an endlessly suggestive film, one that also encapsulates the very promise of motion pictures: to describe and transcend the bounds of time and space. ----- Dennis Lim is the Director of Programming at the Film Society of Lincoln Center. He has written for The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, Artforum, Cinema Scope, and other publications. blog comments powered by Disqus |