| A DEATH IN THE NEIGHBORHOOD

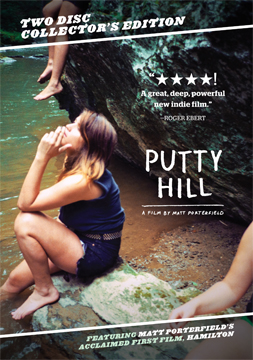

an essay by andrew o'hehir to speak directly to the camera, answering questions from an unseen interviewer. Did he like playing paintball? “I liked it a little.” Who are the other players? “Some of my brother’s friends.” Where is his brother? “He died about a week ago.” When’s the funeral? “Tomorrow.” All the questions that an ordinary moviegoer might ask at this point are, in fact, exactly the right ones. Who is this kid talking to? What kind of film is this, narrative or documentary? Is the movie about the place—a scruffy, workingclass neighborhood on the outskirts of Baltimore—or its inhabitants or what happened to the dead kid? The answer, I suppose, is all of the above, and Porterfield attacks his story directly, avoiding both the clichés of Hollywood narrative and the studied, artful obliqueness of so much independent cinema. Instead of relying on action and dialogue, Porterfield simply has his characters tell us what’s going on: A young man has died, and what we see in Putty Hill are the ripple effects of his death through his family, his circle of friends and his neighborhood. How well you adjust to this wall-breaking combination of dramatic and documentary techniques will probably determine how much you like the movie. This compelling and intimate portrait of the kinds of working-class lives rarely seen in American movies—which also strives, through its style, its unaffected performances and its mode of direct address, to break out of the indie-film audience ghetto—emerged from the wreckage of a coming-of-age feature called Metal Gods, which Porterfield had spent three years preparing in the Baltimore suburb where he grew up. When his funding collapsed in 2009, he repurposed his cast and crew into a collaborative, improvised experiment, which was shot in 12 days and based on a five-page treatment. I’m sure Porterfield was sorry to lose Metal Gods, but what he created in its place hints at an entirely new direction for no-budget, DIY American cinema, and he and the rest of us now owe a strange debt to the investors who pulled the plug. As we meet the cast of characters surrounding the dead Cory and get to know the hard-scrabble places where he lived and died, what emerges piece by piece is a highly complex portrait—sometimes tragic, but also sometimes almost idyllic—of a struggling but resilient community as it confronts an all-too-predictable tragedy. Putty Hill has almost the breadth and range of a classic Robert Altman film and almost the intense formalism of, say, Godard’s 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her, but all of it compressed into less than 90 minutes and focused on a nearly invisible corner of an unglamorous city. For all the film’s formal innovation, what comes through most strongly is its emotional honesty in portraying wounded characters who are neither victims nor anthropological specimens. When Cory’s cousin Jenny (Sky Ferreira) belts a karaoke version of “I Will Always Love You” at his wake, the scene is devoid of satire or kitsch. Instead, a superficial pop anthem becomes a way of saying the unsayable, of expressing devastating heartbreak. If Putty Hill is not yet widely recognized as a breakthrough American film that depicts working-class life with tremendous understanding and no condescension, that says more about our time—when independent film has been pushed to the outer cultural margins and the term “working-class” is generally forbidden—than it does about this extraordinary work. ----- Andrew O’Hehir is a senior writer for Salon.com He has also written about film, books and culture for The New York Times, The Washington Post, Sight & Sound and other publications. |